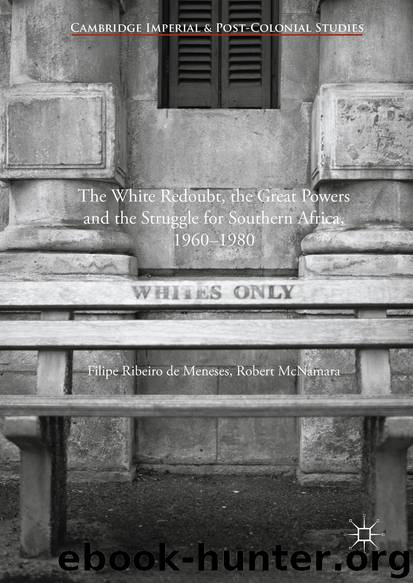

The White Redoubt, the Great Powers and the Struggle for Southern Africa, 1960–1980 by Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses & Robert McNamara

Author:Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses & Robert McNamara

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan UK, London

Rhodesia’s New Challenges

Ian Smith died believing that Rhodesia’s downfall was entirely down to betrayal by the South African government, aided and abetted by Great Britain and the United States. This most unreflective of men, blind to his own hypocrisy and betrayals, frequently delusional and a rebel when it suited, never quite realized that white domination in southern Africa was unsustainable. Rhodesia’s white population was too small and moves towards compromise—the so-called ‘internal settlement’—came far too late.859 Smith rejected favourable settlement terms in 1966 and 1968, which he undoubtedly could have sold to the RF’s white electorate. And there is no doubt that Smith grossly overplayed his hand in securing his virtually concession-free 1971 deal with Sir Alec Douglas-Home, which made inevitable the Pearce Commission’s conclusion that there was no black support for the agreement. His interviews and memoirs betray no suggestion of obduracy or error on his part.860 His extraordinary ability to outmanoeuvre his opponents (and friends) eventually ran into the brick wall of history, with little to show for his efforts.

Rhodesian security forces divide the war against African nationalists into three phases: the Zambezi phase, between 1964 and 1968, during which the threat was easily contained; a lull between 1968 and 1972; and the phase primarily directed from Mozambique by ZANU, from 1972 until 1979.861 Rhodesian intelligence officers later claimed that they were slow to identify the growing links between FRELIMO and ZANU.862 However, ALCORA documentation, the Rhodesians’ insistence on the right of hot pursuit and their repeated calls for the Portuguese to operate more aggressively against FRELIMO suggest otherwise. While the Zambezi provided a natural defence between Rhodesia and Zambia, the dense forest canopy of the Mozambique border was perfect for the infiltration of guerrilla bands to attack white farms and exert increasing control over African villages in Manicaland.

By early 1974, the Rhodesians were increasingly panicked by the deteriorating situation on their border with Mozambique and sought urgent talks between J.H. Howman, their minister of external affairs and defence, and P.W. Botha. The South African ADR in Salisbury, D.P. Olivier, painted a bleak picture: ‘terrorists’ were now a permanent fixture in the northeast, operating in broad daylight. The Rhodesian security forces could neither protect the African population from intimidation nor persuade it to cooperate with the authorities. Olivier felt that they wanted not just more supplies but additional South African manpower, since the Rhodesians had not foreseen the possibility of attacks from Mozambique by ZANU. He noted that the excessive rains and the ‘inertia of our neighbours in Mozambique by no means help’.863 Howman was even more explicit when he met Olivier, focusing on the huge disruption to industry and commerce caused by the calling up of the citizen force.864

The Rhodesians were initially helped by the fact that ZANU did not always pursue the most appropriate tactics. Its fighters focused much of their energy and improved firepower until late in the war on attacking white farms. From the mid-1970s onwards focus was switched to the intimidation of landless African labourers in their villages.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Goodbye Paradise(3810)

Men at Arms by Terry Pratchett(2839)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2518)

Borders by unknow(2315)

Arabs by Eugene Rogan(2301)

Pirate Alley by Terry McKnight(2222)

More Than Words (Sweet Lady Kisses) by Helen West(1867)

Belonging by Unknown(1859)

It's Our Turn to Eat by Michela Wrong(1731)

The Biafra Story by Frederick Forsyth(1656)

The Source by James A. Michener(1615)

Botswana--Culture Smart! by Michael Main(1602)

Coffee: From Bean to Barista by Robert W. Thurston(1547)

A Winter in Arabia by Freya Stark(1539)

Gandhi by Ramachandra Guha(1534)

The Falls by Unknown(1527)

Livingstone by Tim Jeal(1491)

The Shield and The Sword by Ernle Bradford(1410)

Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles by Richard Dowden(1385)